Practically Educated: Past, Present and Future of Engineering Training

Is it possible to build the educational process so that a person can work after the university without long-term adaptation and additional learning?

Graduates of universities and other professional educational institutions are mostly not ready to work “in the field”. Even those who have an excellent theoretical knowledge. It is not surprising: in today’s labour market, person’s knowledge is not as important as his ability to put knowledge into practice. Specialists who are able to immediately engage in a work process and effectively meet the challenges are required.

The reality is that in Russian professional education system the emphasis is still on theory and practice-oriented approach is only making its first steps, in most of the cases – at an experimental level. Under market economy conditions, education remains essentially fundamental. For many years it was considered that such methods form necessary skills as they were developing work potential. An excellent student will become an excellent employee and will have no problems with work. This scheme clearly doesn’t fit modern conditions. The contradiction between professional education system and modern business and industry increases. The country has a huge amount of certified specialists but the market is sorely lacking practice-oriented personnel.

How to solve this problem? The answer is lying on the surface: it is necessary to widely change educational technology, to move away from traditional knowledge transfer to learning with gaining experience. Those new educational technologies should be developed on a basis of practice-oriented approach, which motivates students to acquire professional competency.

The words “practice-oriented education” are frequently seen both in science literature and in normative instruments. According to the definition, practice-oriented training – is a process of mastering an educational program in order to form practical skills by performing practical tasks. Unlike traditional education, which is focused on knowledge assimilation and considers experience more as a learning and cognitive process, practice-oriented education is aimed at gaining practical experience. It may be said that it is standing on 4 pillars: “KNOWLEDGE – ABILITIES –SKILLS – EXPERIENCE” (in opposition to 3 traditional pillars “KNOWLEDGE – ABILITIES –SKILLS”). Thus, a rational combination of fundamental learning, professional and applied education form the basis of practice-oriented training.

Destined by History

As a matter of fact, there is nothing wholly new in practice-oriented training. Actually, the entire educational experience of mankind has led to the unity of theory and practice. Throughout the centuries, learning has gradually evolved from the purely practical “watch and do like me” (as master and apprentice) to scientific “listen, write and repeat” (classical universities). Closer to the 21st century, it became clear that one does not exclude the other.

At the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, classical university education entered its golden age, including Russia. Future representatives of the state elite were learning languages, literature, natural science, mathematics – everything that could be useful for further service in Ministries and Departments. An example of such a classical educational institution is the famous Imperial Tsarskoe Selo Lyceum. Meanwhile, the progress was beginning to tell: science and industry were developed, new territories were reclaimed, plants were built and railways were laid. Everywhere qualified stuff was required, equally possessing knowledge and the ability to apply this knowledge in the real case. Then began the rapid development of the Russian engineering school as a phenomenon that radically changed the approach to higher education.

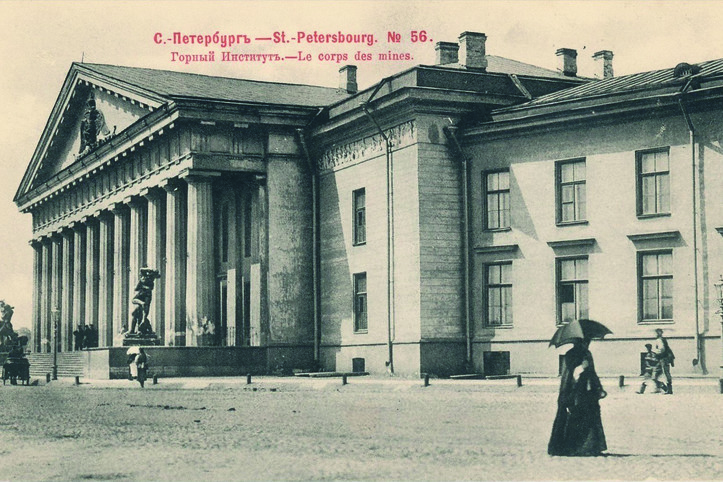

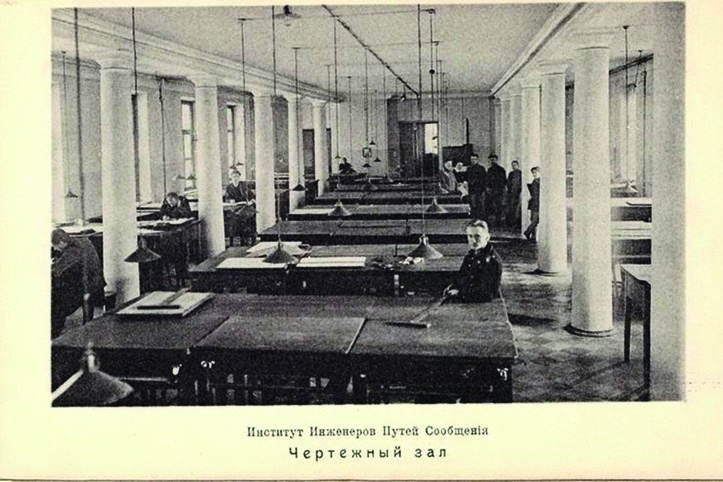

One of the oldest technical universities of Russia was Mining Institute founded back in 1773. In 1804 it was renamed to Mining Cadet Corps. In 1809, Tsar Alexander I founded Institute of the Transport Engineers in Saint Petersburg. In the 30-40s of the 19th century the institute was considered as the strongest technical university in Russia. Education level of its graduates was found eligible for the highest European class of that time. During the 19th century a Moscow Craft School, Imperial Petersburg Institute of Technology, technological institutes in Kharkov and Tomsk and other higher technical educational institutions in different fields of technology were founded. For example, at the Imperial Petersburg Institute of Technology engineers were trained to manage factories.

From the very beginning the principle of the triad “Education – Science – Industry” was put into the base of the Russian engineering school, wherein industry played a key role. Thus, the success of professors of the Institute of the Transport Engineers, which became a benchmark of technical education, was judged on their participation in real construction projects.

The authority of the engineers of that time was huge. It’s no coincidence Nikolai I used to say: “We are engineers”. Nonetheless, most of the industrials couldn’t fully appreciate the advantages of highly qualified specialists over the not educated but well-practiced workers, who were frequently hired for production and construction, especially if they were foreigners. However, as engineer Ivan Bardin pointed out in his notes, those who thoroughly knew what they were doing, were not able to make a deep analysis and, what was worse, did not want to share their skills with colleagues as they considered it as their own capital. Whilst engineer usually needed only a couple of months to be well informed about the process and then he actively improved it using his scientific knowledge.

By the end of the 19th century amid rapid technological development the classical liberal arts education was almost replaced with practice-oriented technical one. Main achievements of the Russian engineering school, including the key idea of uniting education, science and industry, were the base of the industrial development of Russia in the 20th century and after the Russian Revolution in 1917.

The country always needed professionals.

Back in the USSR

Practice-oriented approach also reflected in the pedagogical systems of that time. The most vivid example was system of Anton Makarenko, who today, according to UNESCO (1988), is referred to the four teachers who defined the way of pedagogical thinking in the 20th century. Main years of Makarenko’s activity – 1920-1934 – are notable for the fact that educational institutions at that time were not controlled as tightly as since mid-1930s. There were not so many strict ideological standards and it was relatively safe to experiment. In 1920, Makarenko was in charge of the juvenile reformatory (later named after Maxim Gorky), where he successfully implemented his famous educational pedagogical system.

United in commune of Makarenko’s pupils, ex-street children, whom nobody never needed, were studying the curriculum and at the same time working: they were producing power tools and FED cameras, earning their money. It was a unique experience of labour education and training which, unfortunately, didn’t fit into the soviet reality and had unpleasant consequences for Anton Makarenko. But today the Makarenko’s system is called a model of joint stock company with all employees participating on a mutual basis. In some foreign countries, for instance in Germany and Japan, this system is recommended to the heads of various enterprises.

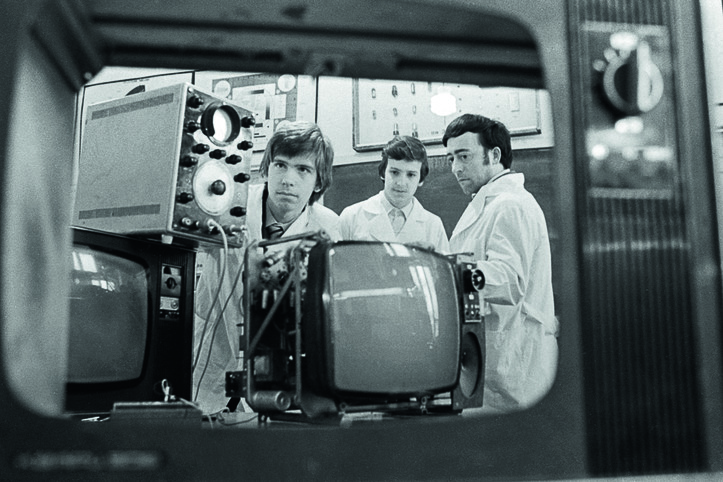

The country always needed professionals. In 20-30s in the USSR there was a so called workers’ faculties where workers and farmers prepared to enter a university. In mid 70s, the VTCs were created – vocational training centres, on which basis students of secondary schools could get primary labour preparation in various specialisations. Right up to the fall of the Soviet Union, there were multilateral relations between educational institutions of professional education and basic enterprises. In many of universities, especially technical, students were offered practical training (academic, industrial and graduation internships), worked the system of post-graduation placement (often to the places of pre-graduation training). All of these ensured an acceptable level of practice-oriented professional training, it was easier for graduates to adapt in the work place and engage in solution of standard production tasks.

In the early 1990s, planned economy ordered to live long. Private enterprises was no more responsible for participation in preparing qualified personnel. Traditional connections broke down, training centres at large organizations were closed. Considering the fact that the same year the country had stopped being the main sponsor for educational service, most of professional education institutions in Russia had to survive rather than develop. Only in the beginning of 2000s the situation began to improve, the question of development and improvement of professional education was as important as economic and strategic problems of the Russian Federation.

Advantages of practical training:

- Increasing the level of determining the eligibility of graduates with the requirements of modern economy and particular employer.

- Mastering an individual set of additional subjects in terms of flexible educational program.

- Shortening the period of studies due to exception of subject that are not connected with professional training.

- Competitive growth in the labour market.

- Shortening the adaptation period in the work place.

- The possibility of getting specialists “on request”, who meet the needs of certain enterprises to the greatest extent.

- The involvement of additional off-budget investments from interested partners to universities.

Practical Training in MAI

Today in MAI a strong theoretical education is supported by the advantages of practice-oriented training. During their learning students are often sent to specialized enterprises, work on course and diploma projects under the guidance of industry specialists, undergo all kinds of internships. This format of training is focused on practical tasks of industry and helps students to see their prospects in enterprises while employers see the ability of future personnel. Moreover, not only students are involved in internships, but teaching staff as well. MAI signed contracts with more than 150 organizations on this type of training.

What Do We Have Today

In 2003, Russia joined the Bologna Process, which requires the necessity of changing the professional education, including higher technical one. As identified by state standards, engineering stuff worker (ESW) should have a system of fundamental knowledge and skills, professional competency, be mobile in professional area and competitive in the world labour market, i.e. fully meet the requirements of market economy.

Consequently, practice-oriented training is no longer something that would be nice to have, but rather sorely needed. Different universities meet this challenge variously depending on their profile, status, location and other factors. In general, today we can highlight four main approaches to practice-oriented education (herewith they can be compatible):

- Organizing educational, industrial and pre-graduate internship for the purpose of students’ professional competences acquisition.

- The introduction of practice-oriented education technologies that contribute to the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the chosen profession as well as necessary personal qualities.

- The creation of innovative forms of students’ professional employment for solving real scientific, practical and pilot-plant works in accordance with the training profile.

- Creating of conditions for acquiring knowledge, skills and experience while learning academic disciplines in order to form student’s motivation and conscious need to acquire professional competency.

It should be noted that practice in practice-oriented approach differ from practice in fundamental education. In the second case, practice is more of a confirmation of a theory’s accuracy, whereas in the first case theory serves as a tool for acquiring practical experience. Of course, for the implementation of practice-oriented approach universities cannot do without permanent business partners who are personally interested in competent training of specialists and consider students as their personnel reserve, participate in the development of educational programs. Support of the state also has a big importance.

An important step was made this year – the Government of the Russian Federation has approved the measures of state support of creation and development of world level research and educational centers (REC) that will combine fundamental and practice-oriented components of education. In 2018, Vladimir Putin talked about the REC system that will abolish the division to universities and national research institutes. In February 2019, the President, in his message to the Federal Assembly, announced the creation of REC in Russia. REC will unite universities, scientific organizations and big enterprises. It will be created taking into account geographical factors and according to competitive advantages of universities joining the REC. The work on these centers is made in the frame of state project “Science”, which will allocate 636 billion rubles. As noted in “Kommersant” newspaper, currently six regions of the country are ready to create RECs, and three of them have already identified partners among universities and enterprises. SIBUR, UMMC-Agro, LUKOIL and Gazprom are all ready to become partners. RECs will have to participate in implementation of research and technology programs, which reviewed by the Councils of priority areas, agreed by the councils of the President for science and education and then approved by the Government of the Russian Federation.

Foreign Approach

Comparing to Russia, the practice-oriented approach is widely spread abroad and is integrant to state educational programs. Although the situation is not similar everywhere. Thus, in leading Asian countries such as Japan, China and Korea there is a classical structure of higher education (bachelor’s and master’s degree), practical orientation in universities is absent. However, it is of importance that, for example, in China universities are aimed at the best of the best high school graduates. Competition, depending on the university’s status, - from 150 to 300 people per place. On top of that, high school graduate must spend 2 years on a preparatory course before applying to university. Those who aren’t ready to compete can enroll in one of the technology-specific schools (equivalent of our colleges), where in 4 years they will get an honourable profession, for example, in fuel and power or pharmacy engineering, forest industry, etc.

Practice-oriented principles in European universities are expressed in a number of special features. Total hours of practical training are up to 50% of all learning time. Specified creative methods are used in education (method of inquiry-based learning, method of projects, etc.), upon that students are oriented to the teamwork from the very beginning. Academic disciplines are focused on creating a holistic view of the future professional activity and most teachers have great experience of practical work. They constantly pay attention to practical activities that they take as a source of upgrade training.

In the USA there are a lot of private professional institutions and even more different academic programs, therefore education is more practice-oriented there. Private universities offer practice-oriented preparation in management, IT, agribusiness and many others. Unlike state universities, private ones don’t live off the state but with the investments of various enterprises and companies that are willing to finance in the training of specialists “for themselves”.

Looking Forward

Today Russian education requires fundamental changes more than ever. Labour market requires students who have already developed necessary skills in a particular industry or business. Main goal of institutions of higher education is to provide decent training of highly skilled practice-oriented specialists who will be able to develop the scientific and production potential of the country, to solve economic and social problems.

The work of institutions should be built in such a way that students can demonstrate their capabilities and talents both in study and real working atmosphere. For this reason leading universities, foremost technical, including MAI, not only use traditional forms and methods of organizing student practice, but also strive to build an environment that encourages students to create start-ups in high-tech fields.Photo Credit: TASS